Legacy of Slavery Art Exhibition

Although slavery is now illegal, it is not a thing of the past.

Modern slavery is a reality for an estimated more than 40 million people globally. Of these severely exploited individuals about 71% are females and one in four are children. Human trafficking – the movement of people through force or deception with the aim to exploit them – is a form of modern slavery. Human traffickers are enabled by the existence of gender inequality, political instability and economic instability. They operate globally, on our continent, and in our country.

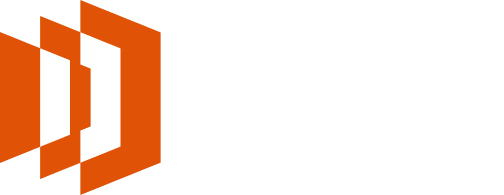

Elton Jagels, Paternoster, Acrylic on canvas, Cape Town Museum Collection

Among the enslaved were many skilled fishermen from the East. The sea was where enslaved fishermen gained a sense of freedom when they were sent out to fish. Enslaved people in coastal areas were also known to supplement meagre diets through fishing.

Post slavery fishing became a traditional occupation for many descendants of people enslaved at the Cape, who passed this skill from one generation to another.

Fishing offered fishermen a shared sense of identity and a sense of community.

Elton Jagels, A Local Fisherman from the Paternoster Community, Acrylic on board, Cape Town Museum Collection

Most fishing communities are poor as their livelihood depends on when the next catch comes in, but the sea is in their blood.

Kenneth Alexander , Fishing at Kalk Bay Jetty, Pen and watercolour on paper, Cape Town Museum Collection

Many enslaved men located in coastal areas were fishermen. Following slavery, they continued to earn a living and support their families as line or trek-fishermen.

Kenneth Alexander , Woman Cleaning Fish at Kalk Bay Harbour, Pen and watercolour on paper, Cape Town Museum Collection

Fish formed a part of the diet of enslaved people at the Cape under the control of the VOC, who 'salted down fish' as food for the 'Company slaves'.

For generations, traditional trek-fishermen were the only suppliers of 'haarders', which constituted a major source of protein for low-income families in the Cape.

Fish would either be bought at Kalk Bay harbour or from the fish cart as local communities would respond to the sound of fish horn.

Peter Clarke, The Boat, Woodcut, colour, Cape Town Museum Collection

Trek-fishing is an age-old tradition that goes back to the days of slavery at the Cape. It is a skill passed from one generation to the other, where certain families were associated with specific trek-beaches. The benefit of the trek extended to the entire community, as there was the opportunity of assisting to pull in the nets during a trek-fishing operation and receive some free fish, a custom widely practised in fishing communities.

The boat is integral to trek-fishing and the role of the 'uitkyker' (look-out man) is vital. At the signal of the 'uitkyker' the trek-operation begins. Some of the crew are sent out on a boat and the 'uitkyker' guides them to the location of the shoal with the use of a whistle and flag. As the boat encircles the shoal the net is cast out over the water.

Trek-fishing has been a traditional way of life at the Cape since the days of slavery.

Elton Jagels, Farmworkers at the End of the Day, Acrylic on board, Cape Town Museum Collection

The San and Khoekhoen at the Cape were hunter-gathers and herders. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) forcibly replaced the precolonial hunter-gatherer and herding economies with a commercial agricultural economy. The labourforce on these colonial farms were enslaved men and indentured Khoekhoe and San people.

Many of the farmworkers at the Cape today are descendants of either indentured Khoekhoe and San people or people who were enslaved at the Cape.

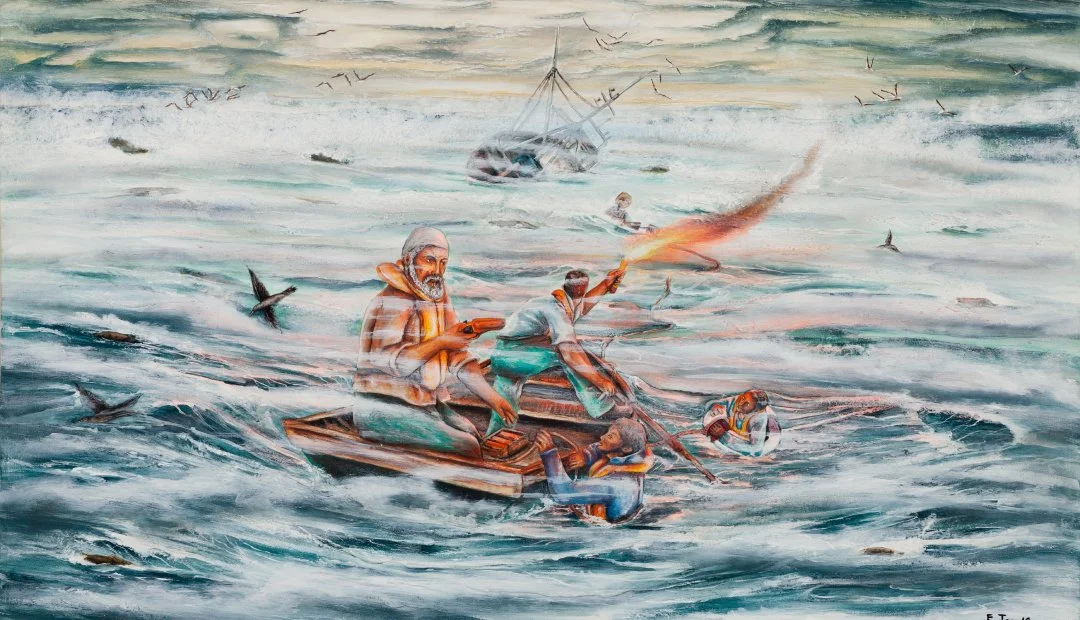

Kenneth Alexander , Talking to the Moon, Pen and watercolour on paper, Cape Town Museum Collection

Enslaved men experienced the trauma of emasculation: they were referred to as 'boys' and not men. They had no power to protect their families who could be taken away from them at any time. They were also induced into alcohol dependence, which destroyed their confidence and shattered their dreams.

They were kept submissive by the evil 'dop' or tot system, which arrived with the regularity of the slave bell. Historian, Robert Shell described the 'dop' system as the "division of the day into 'dop’, work, 'dop', work, and 'dop'."

For these people it would seem that alcohol offered a mental numbing against an oppressed existence from which they felt unable to escape, but through which they and their descendants were ultimately destroyed. While there are many people who have managed to overcome this, there are still others for whom this legacy has created a brokenness, an unending despair.

Kenneth Alexander, Seamstress, Oil pastel on paper, Cape Town Museum Collection

The historian Robert Shell stated that enslaved women from the East, particularly Bengal, the coast of Coromandel, Surat and Macassar were in demand because of their skills as seamstresses.

He described that on entering eighteenth-century Cape homes visitors were greeted by the sight of "a long, broad gallery where four or six 'slave' women sat on small wooden benches, sewing or knitting."

Post slavery many formerly enslaved women supplemented the family income as dressmakers, while their descendants worked in local factories such as Rex Truform.

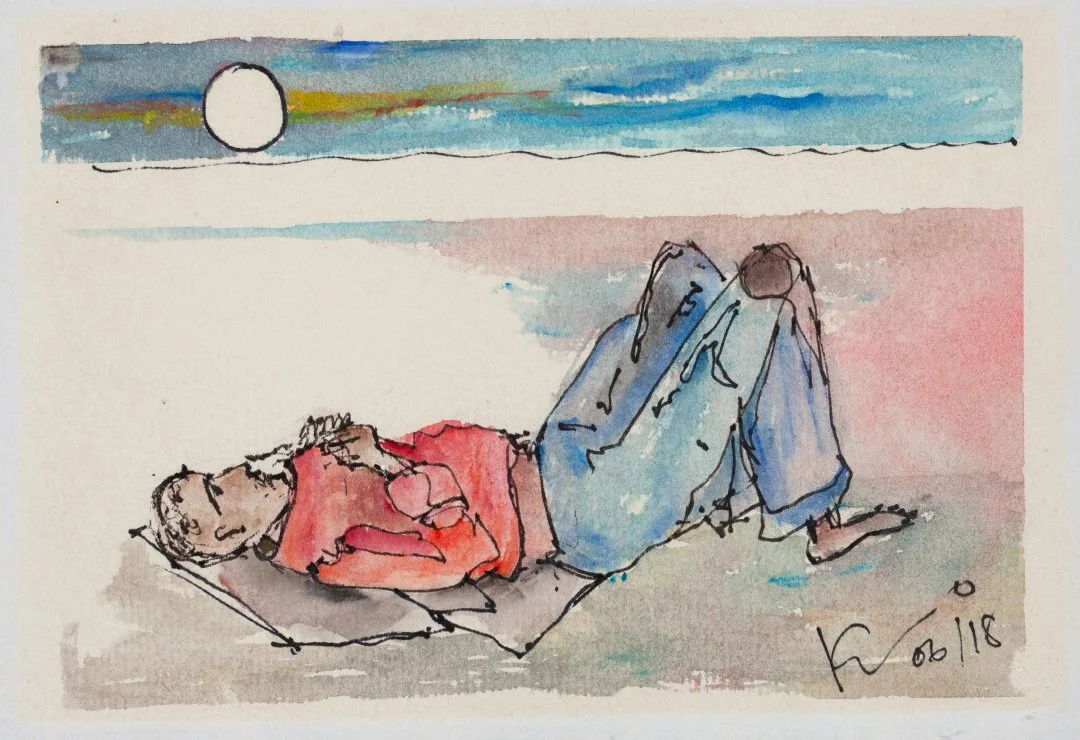

Peter Clarke, Sewing Lesson, Drawing in pen and carbon, black and white, Cape Town Museum Collection

Slaveholding households benefited from the skills of enslaved seamstresses who sewed the family clothes. Following slavery highly skilled seamstresses were able to earn a living from home and pass their skills on to the daughters.

Tony Grogan, Washerwomen, Watercolour, Cape Town Museum Collection

Post emancipation, many formerly enslaved 'washerwomen' took in washing to supplement the family income. This was particularly the case for the wives of fishermen, whose livelihoods were seasonal.

Nanette Gordon, Untitled, Acrylic paint on canvas, Cape Town Museum Collection

Sexual violence was experienced by enslaved women, both in private homes and in the Slave Lodge in town, which functioned as a brothel at night.

The violation of the bodies of enslaved women was normalised during slavery and has been transported into contemporary South African society where gender-based violence against women is a growing problem.

Cheslyn Brandt, Grysie, Acrylic in frame, Cape Town Museum Collection

Slavery was a traumatic experience for enslaved people, whose daily experiences were overshadowed by violence, or the threat of violence. Because of family separation, for many enslaved people the experience of family life was not possible. The psychological impact of the trauma experienced by enslaved people has had intergenerational consequences and continues to reverberate through our society today.

Amos Langdown, Two Women with Babies, Drawing, colour, Cape Town Museum Collection

Slaveholders used the most painful mental cruelty possible to control, punish or hurt enslaved women: separating them from their children.

Tyrone Appollis, Mother and Child, Linocut, black and white, Cape Town Museum Collection

The historical trauma of family separation and the lack of experience of family life have had far-reaching intergenerational consequences for subsequent generations.

Kenneth Alexander, Daisy Kadibil, Watercolour, Cape Town Museum Collection

Daisy Kadibil was an aboriginal Australian woman who as a child was one of the 'stolen generation' of children forcibly separated from their parents by the Australian Government. Her story is recorded in the movie The Rabbit Proof Fence.

However, her experience resonates with those of enslaved children who were separated from their mothers in their formative years.

Her ravaged face reminds us of the universal historical trauma carried by people who were separated from their parents as children, whether indigenous or enslaved.

Leetham Jacobs, Cape Town, Pencil on paper, Cape Town Museum Collection

Cape Town has a special meaning for the descendants of enslaved people.

"It is the city that has shaped our unique historical legacy and it is our home. This city is carved into our psyche in a manner that is unimaginable for those whose history was shaped differently. It is the city of our haunted experiences, but also the city of our longing, hopes and dreams. Cape Town is our birthright, our mother."

Joline Young, Historian and descendant of enslaved people at the Cape.

Tyrone Appollis, District Six, Gouache, colour, Cape Town Museum Collection

District 6 was a lively community of diverse people, many of whom were formerly enslaved people who settled here post emancipation. With the emancipation of slavery, slaveholders were paid compensation from Britain, however, enslaved people were not given any financial assistance to restart their lives as free people.

Extended families, strong community bonds and reciprocal sharing helped poor communities to survive circumstances of extreme poverty. The elders kept a watchful eye over the children.

Overcrowded living conditions due to poverty meant communal living and sharing of space and resources.

In 1966 the journalist Brian Barrow wrote of District 6:

"Go into one of the fruit and vegetable shops and you soon realise how the very poor manage to live. In these shops people can still buy something useful for 1d [penny]. They can buy one potato if that is all they can afford at the moment, or one cigarette. You can hear them ask for an olap patiselli (a penny’s worth of parsley), a tikkie [tiekie] tamaties or a tikkie swartbekkies (black-eyed beans), a sixpence soup-greens, an olap knofelok (garlic) or olap broos, which means a penny’s worth of bruised fruit."

Tony Grogan, 'Malay' Quarter, Wash Day, Watercolour, Cape Town Museum Collection

Post emancipation, Bo-Kaap became home to many formerly enslaved people who formed the tight-knit Bo-Kaap community. Today this community, where Islam is practised, faces the challenges posed by gentrification.

Tony Grogan, Bo-Kaap, Watercolour, Cape Town Museum Collection

Although once home to both Christian and Muslim people, for many years Bo-Kaap was known as the 'Malay' Quarter. Small cottages nestled beneath the mountain and overlooked by the minaret of the mosque, from where the community heeded the call to prayer of the Athzaam.

Tony Grogan, Under Lion’s Head, Watercolour, Cape Town Museum Collection

A view of Bo-Kaap nestled under Lion’s Head.

Following emancipation enslaved people settled into the area and formed a close-knit community.

A noted former resident of Bo-Kaap was the historian Achmat Davids. According to him, "the colonised people of the Cape had played a major role in developing Afrikaans".

Albert de Jager, On Wash Day, Drawing in mixed media, black and white, Cape Town Museum Collection

Children in Bo-Kaap playing freely under the watchful eye of adults in the community.

While the Bo-Kaap community were saved from forced removals in the 1960s. In present day South Africa, this community faces the crisis of disintegration due to gentrification.

Léshaan Moses, Dodging Bullets, Acrylic paint, pencil and pen, Cape Town Museum Collection

The National Party came into power in 1948. Between 1955 and 1957 the apartheid spatial planning machine sounded the first rumblings of change as people from the inner city were forced into segregated townships on the Cape Flats on the basis of race. This was followed by a vigorous 'Master Plan' devised by the apartheid government in 1966. Its aim was to clear greater Cape Town of all dark-skinned residents. The plan was to relocate people from urban areas in Cape Town to high density industrial type buildings on the Cape Flats and develop what was described as "a future Coloured City".

The greatest casualities of the forced removals were the youth. Don Pinnock describes the impact of forced removals on young people, saying that "poverty and apartheid's massive social engineering created stresses to which gangs were a teenage response".

In this painting the artist Léshaan Moses depicts the violence of gang initiation. However, through initiatives like the Heal the Hood Project started by Emile Jansen in 1988, many young people are finding a positive alternative to gangsterism through dance, music and art.