Enslaved Lives

The Dutch 'slave' ship Leijdsman arriving in Madagascar, 1715. Image: C 2246, Western Cape Archives and Records Service

Slavery at the Cape impacted thousands of people and their families. Between 1658 and 1807, 63 000 people were snatched from their homes and brought to the Cape as forced labour for the expanding settlement by the Dutch East India Company (VOC), and later the British colonial authorities. The people enslaved at the Cape came from Madagascar, South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Africa, and during the early VOC period at the Cape some were brought in from West Africa.

The lived experiences of enslaved women, men, and children at Leeuwenhof provide glimpses of what it meant to be a 'slave' at the Cape.

'Slaves' doing some of their daily work. A bound enslaved man can be seen in the foreground, 1764. Image: M 166, Western Cape Archives and Records Service

Violence, both physical and psychological, was built into the experience of slavery at the Cape.

After being forcibly separated from their families and friends in their birth countries and alienated from their cultures, languages, and religions; enslaved people were made the 'property' of others. They had no rights to their own children and no means to protect them; they could not own property; and did not have the freedom to choose who they wanted to work for or the kind of work they wanted to do.

Enslaved labourer working on farm, 19th century. Image: A 3007, Cape Archives and Records Service

The Cape's growth as an agricultural economy was built on the labour of enslaved people.

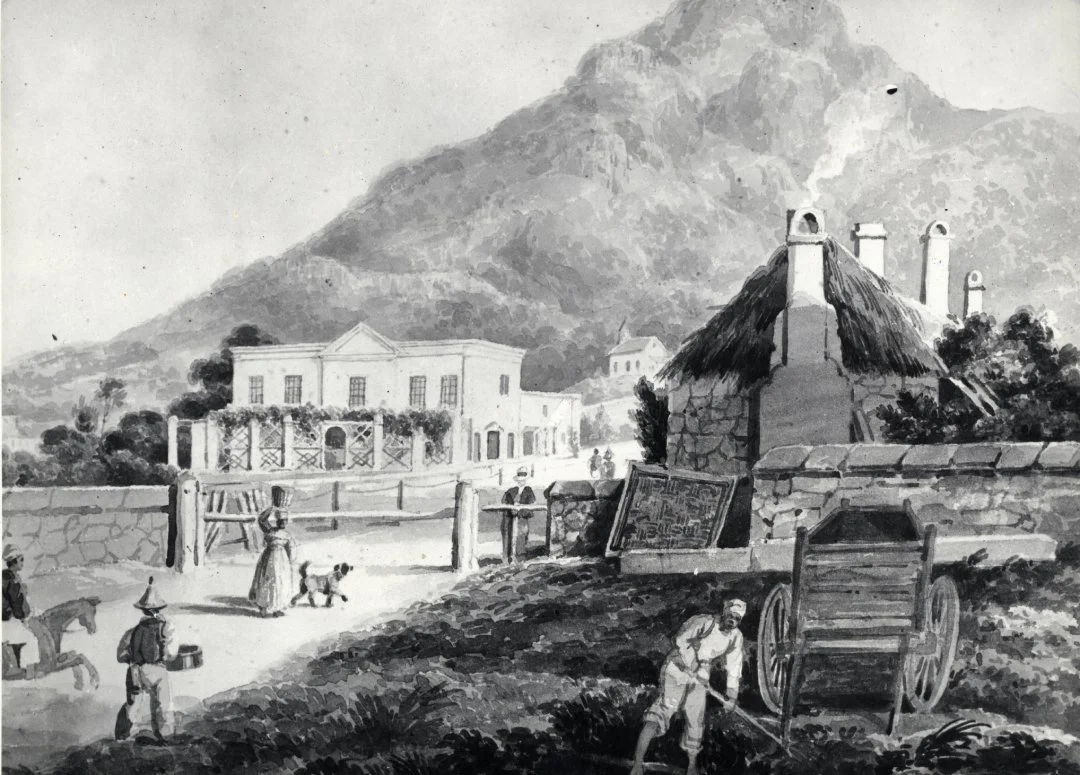

Cape Town farms, including Leeuwenhof, and market gardens, 1820. Image: E 263, Western Cape Archives and Records Service

Leeuwenhof was originally granted to Guillam Heems in 1693.

Johannes Zorn was the registered owner of Leeuwenhof between 1799 and 1825. By 1807 he owned 54 'slaves' and in 1820 the 'slave' quarters at Leeuwenhof were built. Zorn was a member of the Cape elite, whose wealth was built on the exploited labour of enslaved people.

Archival records show that Leeuwenhof's 'slaves' came from Batavia, Bengal, Macassar, Madagascar, Mozambique, and Mauritius. Some were people born into slavery at the Cape.

'Slave' auction notice, 1829. Image: National Library of South Africa

Enslaved people were regarded as economic assets who could be mortgaged, sold, or hired out for profit.

By the end of the 18th century the following Leeuwenhof 'slaves' were valued or bought at the following prices:

Adonis of the Cape – 300 rixdollars, Philida, January, February, Maart and April, all from Mozambique – 500 rixdollars each, Simon of Mauritius – 550 rixdollars, and Domingo of Mozambique – 743 rixdollars.

"Slaves [at the Cape] were auctioned alongside pieces of household furniture, farm equipment and livestock, the essence of their humanity denied". Tracey Randle, 2017

'Slave' auction notices, 1801. Image: National Library of South Africa

At the beginning of the 19th century, Zorn bought Simon of Mauritius from Jan Pieter Baumgardt. He would possibly have been advertised in a similar 'slave' auction notice.

Farm 'slaves', 19th century. Image: A 3122, Western Cape Archives and Records Service

Both the household and the farm work done by enslaved women and men was hard. They had to toil continuously throughout the year, with little time for rest.

"I am always working; I need to rest sometimes".

Slammat of Bougies, an enslaved farmworker, 1795

Enslaved labourer, 1719. Image: Parliament of South Africa

The majority of Leeuwenhof's enslaved labour force were male labourers. In 1816, Zorn had 15 labourers who came from Mozambique, Madagascar, and the Cape.

Enslaved labourers threshing wheat, 18th century. Image: Parliament of South Africa

Louis, Joseph, Michel, Francois, Mozes, Pero, April, Pietjie, January, Africa, Scipio, Sabel, Patientie, November and Moses; worked long hours every day, doing heavy and back-breaking work.

This included tending their 'owner's' horses, cattle, goats, and pigs; planting and tending his vines and pressing grapes to make wine as well as sowing, harvesting, and threshing his wheat.

Enslaved labourers pressing grapes for wine, 1832. Image: Parliament of South Africa

The same 'slaves' tending the vines and pressing the grapes, received regular portions of wine throughout the day. This destabilising 'dop' or tot system was well established at the Cape by the 18th century.

"The devastating repercussions of this form of labour control through alcohol dependency continues to affect communities into the present".

Tracey Randle, 2017

View from Leeuwenhof's garden towards Cape Town, 1710. Image: M 1 – 000985 – 01, Western Cape Archives and Records Service

Leeuwenhof's ornamental and market gardens would have been tended by enslaved gardeners. In 1816 the gardeners included Cato and Snap who were both from Batavia. Cato was already 70 years old at the time.

Green Market Square, early 19th century. Image: A 2999, Western Cape Archives and Records Service

Some of the produce from Leeuwenhof's market garden was sold in town by the enslaved hawkers named Azor of Madagascar and Baatjie of Batavia.

The profit they made belonged to their 'owner'.

Augustus van Bengalen, the enslaved servant of the slaveholder Hendrik Cloete, holding his pipe, 1788. Image: Rijksmuseum

In 1816, Zorn’s family had seven enslaved 'house boys'. Philip, Frederik, William, Carli, Louis, Dam and Patientie, aged 70. They came from the Cape, Batavia, and Bengal.

They would do domestic work or any personal tasks their 'owner' required.

These adult men had to endure the humiliation of being called 'boy'.

The wealthy Storm family and their 'slaves' in Cape Town, 1760. Image: Stellenbosch Museum

By 1816, Zorn's large slaveholding included two male cooks from Mauritius named Francois and Apol, as well as two coachmen: the locally born Siloa and Pieter from Madagascar.

Zorn also 'owned' highly skilled enslaved people. Caesar from Madagascar and Mey from Batavia were masons. September of Batavia was a shoemaker.

These men may not only have worked for Zorn, but their services were possibly hired out for his profit, a common practice at the Cape.

After September was freed in 1818, his shoemaking skills may have enabled him to start his own business.

Deed transferring Adonis of the Cape to Roosje of Batavia, 1797. Image: NCD 1.38 no 162 p 1, Western Cape Archives and Records Service

The economic benefit of enslaved labour was for the direct benefit of the slaveholder. This is visible in the conditions under which Hendrik Johannes Fehrsen, an earlier owner of Leeuwenhof, agreed to transfer his 'slave', the locally born Adonis of the Cape, to the 'free woman', Roosje from Batavia in 1797. The conditions stipulated that Adonis had to continue making clothes for Fehrsen's family without receiving payment. Roosje was not allowed to either profit from his skills or sell him. Instead, she had to agree to make provision for the amount necessary to buy his freedom after her death.

Enslaved washerwomen doing laundry on the slopes of Table Mountain during the early 19th century. Image: A 3015, Western Cape Archives and Records Service

Zorn's family had nine 'house maids' working for them by 1816. They were Sericus from Mauritius who was already 60 years old, as well as Regina who was only 12 years old, Spasie, Christina, Sara, Doortjie, Marietjie, Diana, and Rosina, who were all locally born into slavery.

Christina deserted sometime later.

Deserting was one form of personal resistance to slavery. Other forms of resistance to slavery by enslaved people included arson and even suicide.

Enslaved child made to fan a farmer's wife while she drinks her coffee, 1806. Image: Parliament of South Africa

The treatment of enslaved people at the Cape varied greatly and depended on their individual 'masters'.

The clothes provided by their 'owners' clearly distinguished the Cape's enslaved people from free people. Significantly, enslaved men were not allowed to wear shoes.

There was no legislative control over the food given to enslaved people until 1823. Some visitors to the Cape wrote that many of the privately-owned enslaved people were well fed, often eating the same food as their 'owners'. However, others were so poorly fed that hunger led them to steal food for themselves and their children.

Enslaved labourer without shoes, dressed in worn clothing, 19th century. Image: Western Cape Archives and Records Service

In 1808 a Russian visitor wrote,

"the slaves in this colony are kept very poorly - they are dressed in rags, even those who serve at the table of their masters".

Indentured Khoekhoe labourer busy ploughing; with enslaved labourers in the background, 1719. Image: Parliament of South Africa

There was little difference between the treatment of enslaved people and the Khoekhoen, who were indentured to Cape colonists and forced to do household or farm work.

Enslaved seamstress, 19th century. Image: National Library of South Africa

Zorn's female 'slaves' would have done the housework, sewing, cooking, laundry, and childminding.

Enslaved cook preparing food, 19th century. Image: National Library of South Africa

It was common practice at the Cape for enslaved women to sleep near the hearth in the kitchen. This was likely the case at Leeuwenhof before the 'slave' quarters were built. Enslaved women, isolated in this way, were made vulnerable to sexual exploitation.

Enslaved builders at the Cape, beginning of the 19th century. Image: AG 15689, Western Cape Archives and Records Service

While we do not know the names of all the enslaved people whose labour contributed to the building of the Leeuwenhof manor house and the 'slave' quarters, the contribution of their labour in constructing these historical buildings should be honoured.

The 'slave' quarters used to have "old slave beds built into [a] wall [of the] left-hand back room" and originally also contained stables.

Enslaved washerwoman carrying her child on her back, 1812. Image: Parliament of South Africa

Enslaved couples and their children could be separated at any time as they were sold separately from each other. These traumatic events were very emotionally damaging for enslaved people, as they were not ensured of having lasting relationships and experiencing stable family lives.

In August 1825 Zorn sold his enslaved 'housemaid' named Marietjie to P.L. Cloete of Cape Town. Marietjie of the Cape had lived at Leeuwenhof for at least nine years and gave birth to five of her children there. Her infant daughter Christina was buried at Leeuwenhof. Only three of her children were sold with Marietjie: five-year-old Frans, three-year-old Christiaan, and two-month-old Frits. The heartache felt by Marietjie when she had to leave her eight-year-old daughter Coba behind is unimaginable.

Enslaved individuals walking arm in arm in Strand Street, 19th century. Image: A 3000, Western Cape Archives and Records Service

Throughout the history of slavery at the Cape, enslaved people formed unions and had families. These family bonds were fragile and vulnerable to the whims and decisions of slaveholders. They could be broken at any time, leaving enslaved people traumatised as they pined for their loved ones.

Only from 1823 onwards were enslaved people, who were baptised into Christianity, allowed to be legally married. However, enslaved couples practicing Islam found some dignity in Muslim marriage ceremonies, although their unions were not recognised by law.

In December 1799 Zorn and Cornelia Theron, widow of the previous owner of Leeuwenhof, Johan Michiel Elser, stood surety for a Cape born enslaved family. They were 'the freed slave Jacob', his companion, the 'free woman' Victoria, and her child Hendrik. This formerly enslaved family had to promise that they would all be baptised together, and not to request any financial support or be a burden to the Cape authorities for a period of 20 years.

Enslaved 'wet nurse' breastfeeding her 'owner's' baby while her own young child sits neglected at her feet, end of 18th century. Image: National Library of South Africa

Enslaved women's bodies belonged to their 'owners', despite having life partners and children.

Enslaved women were made to breastfeed and care for their 'owners'' children while being forced to neglect the care and needs of their own children. There were also incidences where their 'masters' would force them into having sex with false promises of freedom for themselves and their children. In these and many other ways, enslaved women were at risk of mental and physical abuse from both the mistress of the house and their own partners. The psychological cost of such traumatic experiences to themselves and the consequent intergenerational trauma to their children is immeasurable.

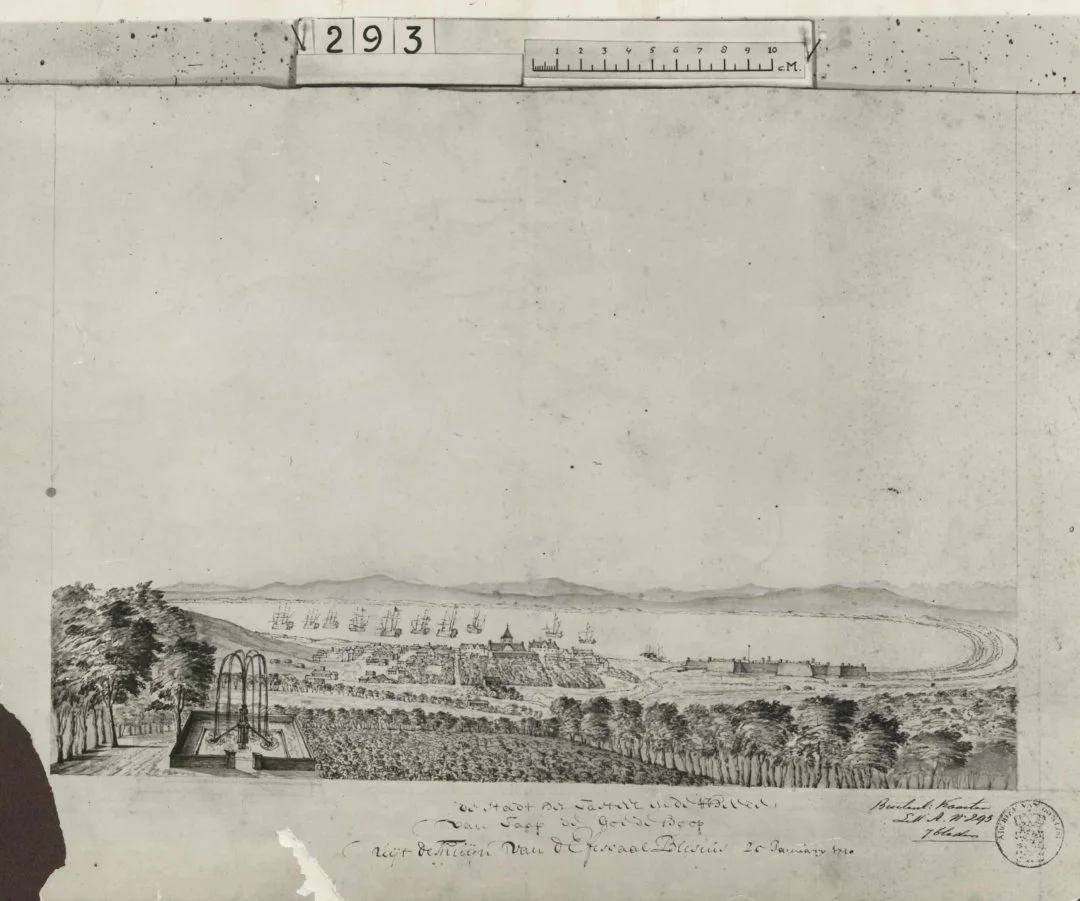

Two generations of female descendants of formerly enslaved people in the early 20th century. Their names were not recorded. Image: Stellenbosch Museum

Throughout the period of slavery at the Cape, not a single man – enslaved or free – was found guilty of the rape of an enslaved woman.

The repercussions of the physical and sexual assault of enslaved women continues to reverberate through our communities to this day in the form of unconscionable levels of gender-based violence.

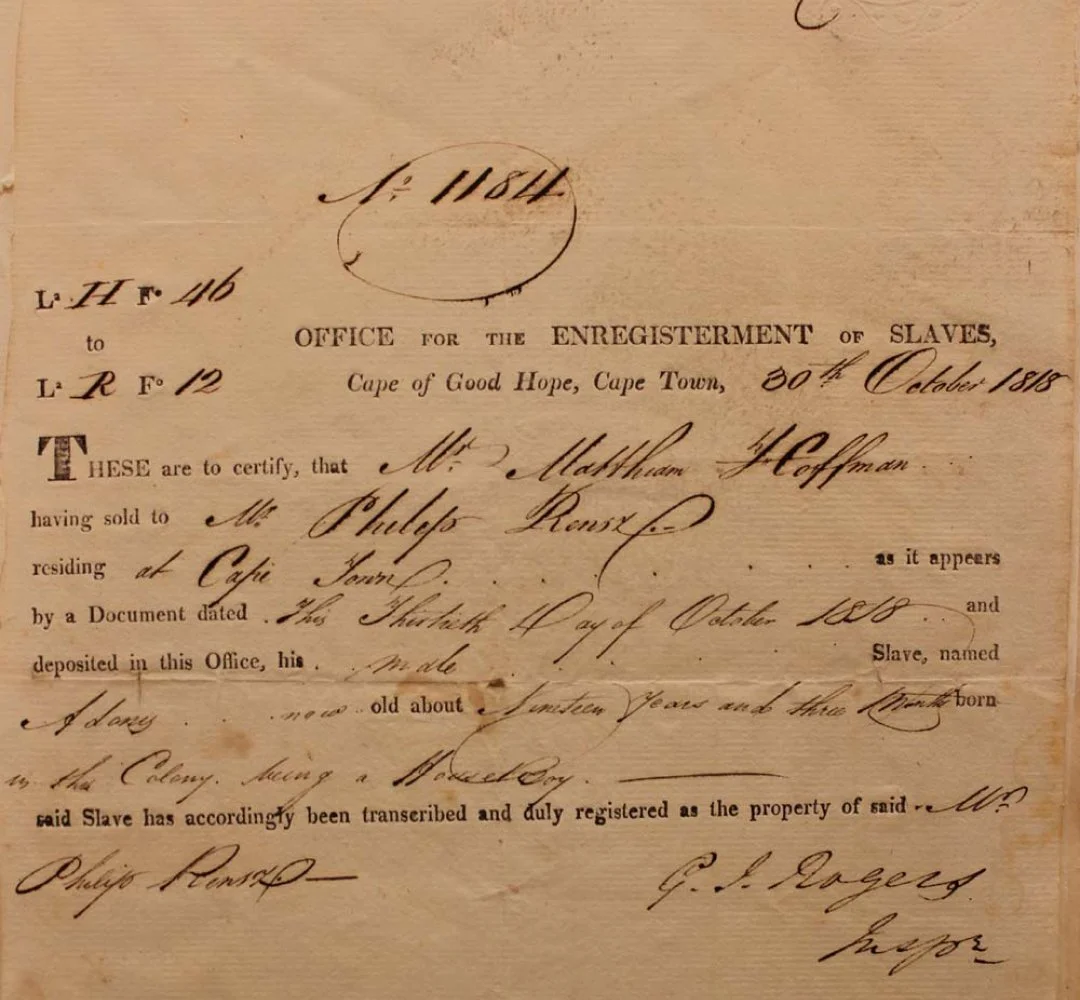

Registration of a locally born male infant as the 'property' of his 'owner', 1826. Image: Parliament of South Africa

Children born to enslaved women, including children fathered by the slaveholder, were born into slavery, and regarded as their 'owner’s' 'property'. However, if the slaveholder married the enslaved woman or legally adopted the child, her and her children’s status would change from enslaved to free.

Unlike their mothers, enslaved children’s enslaved fathers were not listed in official documents, another indication that colonial officials and slaveholders did not recognise or respect the family life of enslaved people.

Enslaved mother and infant, 19th century. Image: Western Cape Archives and Records Service

Twenty enslaved children were born at the Leeuwenhof Estate between 1816 and 1833. They were regarded as the legal 'property' of Johannes Zorn and later his widow Catharina Christina Scheller: their names were Pierre, Saartjie, Lena, Coba, Adriaan, Christina, Isaac, Albert, Jacob, Frans, Christiaan, Carolina, Ram, Lucrees, Louisa, Elias, Frits, Sara, Thomas, and Regina.

William of the Cape was one of the many enslaved children who was denied a normal childhood, having worked as a 'house boy' at Leeuwenhof from the age of ten.

Anna de Koningh. Image: E 313, Western Cape Archives and Records Service

From the early days of settlement at the Cape until well into the 18th century there were marriages between freed formerly enslaved women and European men. Many South African family trees have grown out of these unions.

Anna de Koningh was born into slavery in Batavia and arrived at the Cape with her enslaved mother, Angela of Bengal, in the second half of the 17th century. In 1678 Anna married Oloff Bergh who was a prominent VOC official. Ironically, Anna became a 'slave owner' herself and at the time of her death she was recorded as 'owning' 27 'slaves'.

Johanna Magdalena Bergh, daughter of Anna and Olof, married Daniel Godfried Carnspeck who owned Leeuwenhof from 1740 onwards.

This daughter of a formerly enslaved woman farmed Leeuwenhof for twenty years after her husband's death.

Anna, through her daughter Johanna Magdalena and her eleven other children, became one of the country's matriarchs to which many diverse South Africans can trace their lineage.

19th Century poster of the "Heroes of the Slave Trade Abolition". Image: National Portrait Gallery, Wikimedia Commons

Towards the end of the 18th century economic factors, humanitarian campaigns, religious debates questioning the morality of slavery, and growing resistance by the enslaved became the driving forces behind international attempts to end slavery.

Abolitionists often used graphic images like this child being dragged away from its mother at a 'slave' auction in Cape Town in 1824 to illustrate the cruelty of trading in people to the public. Image: National Library of South Africa

From the 1760s various British human rights activists, humanitarians and religious leaders fought a long, hard battle to end slavery. Pro-slavery campaigners painted a false picture of happy and well-treated enslaved labourers and servants. According to them the lucrative trade in human beings was essential to the British economy.

Olaudah Equiano was enslaved as a child in the Kingdom of Benin (now southern Nigeria) and had to work for different slaveholders before buying his own freedom in 1766. By the 1780s he was a writer living in London and a leading voice among British abolitionists. He published one of the few personal accounts of being enslaved. Image: British Library, Wikimedia Commons

Due to the efforts of the abolitionists a stronger anti-slavery sentiment developed in Britain. Formerly enslaved Africans like Olaudah Equiano who lived in Britain emphasised the inhumanity and horrors of slavery by sharing their lived experiences. Other abolitionists argued that the slave trade no longer made economic sense and was becoming less lucrative than before.

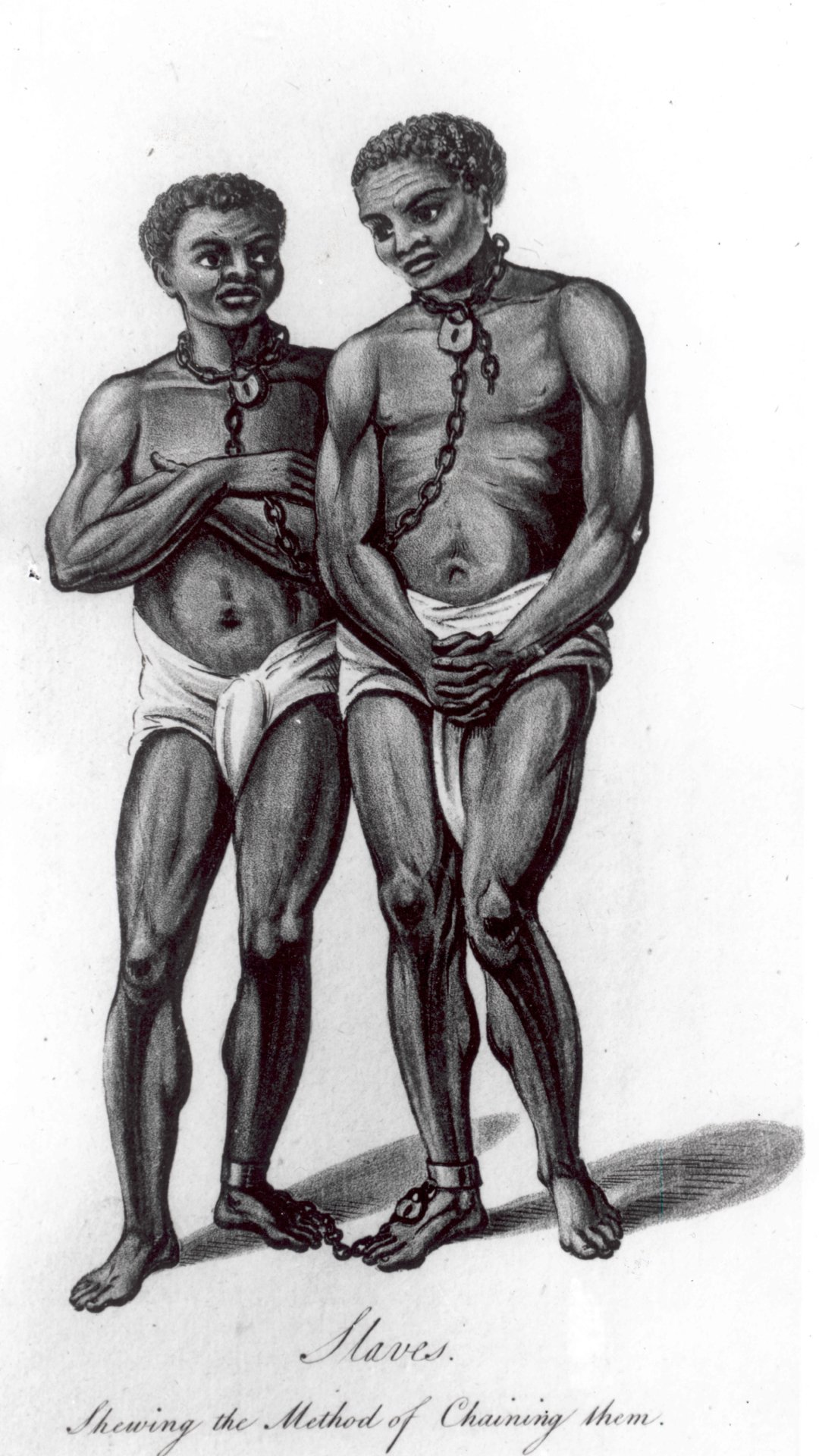

"Slaves. Showing the Method of Chaining them". Image: M 375, Western Cape Archives & Records Service

Eventually public support in Britain for the abolition of slavery became so strong that it could no longer be ignored and in 1807, the British Parliament finally passed an Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

The Act did not end slavery – only the slave trade. Enslaved people were still not free, and the economic benefits of slavery continued for slaveholders. Illegal slave trading also continued for decades more.

Registration of a Cape born enslaved person as the 'property' of his 'owner'. Image: Parliament of South Africa

By 1807 the Cape was part of the British Empire and therefore influenced by decisions made in London. The British ban on the slave trade meant that no more enslaved people could legally be sent to work at the Cape. Those already enslaved here, and their new-born children however remained the 'property' of their 'owners' and could still be sold.

Ordinance 19 of 1826. Image: National Library of South Africa

Over the next few years Britain introduced more laws to improve the lives of the Cape's enslaved (amelioration laws) and conditions improved for some.

Some slaveholders ignored these reforms and laws for the protection of the enslaved and continued to ill-treat their 'slaves'. While some enslaved people made legal complaints about their 'owners', many were unable to report their ill-treatment to the Protector and Guardian of Slaves appointed by the colonial government.

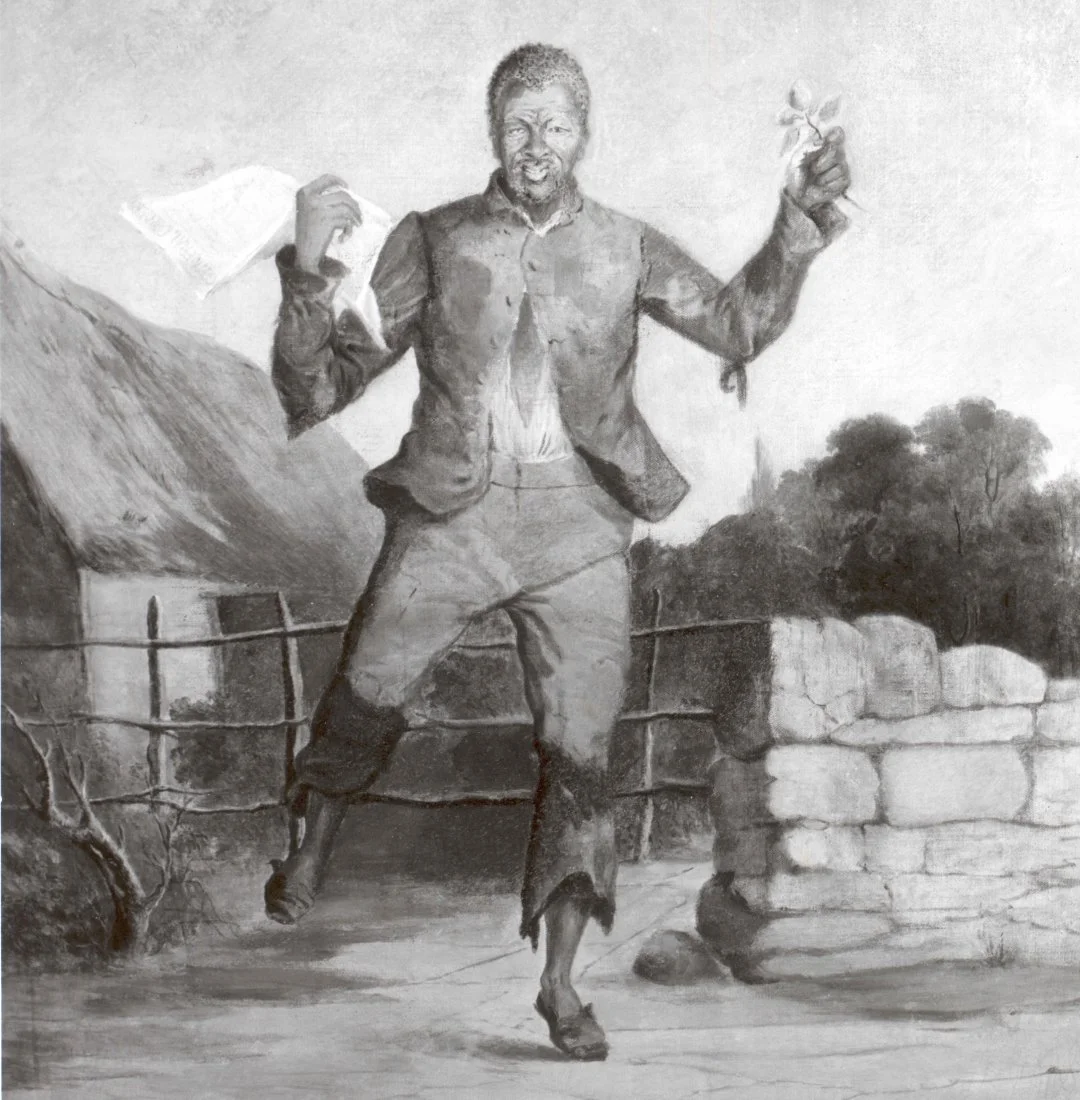

19th century illustration symbolising emancipation. Image: National Library of South Africa

The end of slavery at the Cape was the result of a decision from outside rather than internal influence. There was little support from local slaveholders for the abolition of slavery. Instead, they strongly opposed any measures towards amelioration and emancipation.

Abolitionists relentlessly lobbied for an end to slavery while the resistance, rebellions, and revolts by the enslaved intensified.

Some British policy makers championed human rights inspired by the Enlightenment and revolutions for fundamental rights and freedoms. Others were convinced that slavery would soon become less lucrative with the expected decline of the plantation system. A combination of these factors eventually resulted in legislative change to end the centuries old practice of enslavement.

"Procession on the occasion of the slave liberation, Cape Town". Image: E 3303m Western Cape Archives & Records Service

Slavery finally became illegal when the Abolition of Slavery Bill was passed by British Parliament in 1833. On 1 December 1834 local enslaved people were emancipated from slavery. However, they were made to serve a four-year 'apprenticeship' (in name only). This protected the interests of slaveholders rather than that of their 'freed' workers whose enslavement was effectively extended until 1838.

For some enslaved people, like November of the Cape, who was an enslaved labourer at Leeuwenhof, emancipation would come too late. He passed away at the age of 63 just four months before emancipation.

The Leeuwenhof homestead and vineyard, early 20th century. Image: E 8460, Western Cape Archives and Records Service

After emancipation, the previously enslaved of Leeuwenhof must have been hopeful for a better future. However, after the end of their 'apprenticeship', most of the Cape's formerly enslaved people were freed into abject poverty.

Farmworkers, early 20th century. Image: Worcester Museum

Although the slaveholders received compensation from Britain, none of the formerly enslaved people received any support to start their 'new' lives. This left them with few options, such as to join the mission stations or to continue working as wage labourers in much the same conditions as before.

Manisa in 1914, Cape Times Weekly Edition. Image: National Library of South Africa

"…after [emancipation] we would hire ourselves to a good ['master']; and that's where it was good to be free".

Manisa of the Cape, 1914.

Many formerly enslaved women walked from place to place trying to find their children and other family members who had been sold away from them. Some families were lucky to be re-united, but many were not.

Anna Thembo with Henrietta Schreiner. Image: Worcester Museum

Some of the formerly enslaved and their descendants would dedicate their lives to helping their communities and the destitute of Cape Town. Anna 'Sister Nannie' Thembo (also Tempo) was the daughter of formerly enslaved parents from Mozambique. From 1914 Anna helped Cape Town’s stranded and destitute women and girls. She eventually established the Sister Nannie Rescue Home for Homeless and Friendless Girls where they were given shelter and took in laundry to cover expenses while looking for work as domestic 'servants'. "Nannie-huis" became a beacon of hope for many in the centre of town until it had to move to Athlone in 1960.

Unnamed cabinetmaker, Plumstead. Image: AG 13253, Western Cape Archives and Records Service

Social stratification existed among the formerly enslaved. The highly skilled were better placed to create better living conditions for themselves and their families. These were men who had skills such as masonry, shoemaking, tailoring, cabinet making and carpentry. They typically moved to cottages in town to start their own businesses. Many became prosperous, but decades later their families would be torn apart again by the forced removals during apartheid.

The names of these formerly enslaved people were not recorded. Their photographs were simply captioned, "ex-'slave' who was nurse to John Ross’s children" and "elderly freed 'slave'." Images: AG 12834 & AG 4653, Western Cape Archives and Records Service

An enormous social divide existed at the Cape between people who were enslaved and those who were not. This meant that the details of enslaved lives were seldom recorded as they were of little significance to the majority of colonial officials and free people. Little changed in this regard post-emancipation. We therefore do not currently know what became of the formerly enslaved from Leeuwenhof. In future we may learn more about them from stories that may have been passed down in their descendant families, or other research.