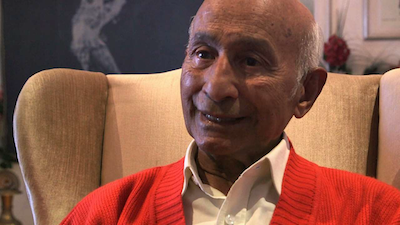

Johaar Mosaval

From District Six to the Royal Ballet

District Six like Harlem in New York also had its own “Harlem Renaissance” or cultural boom. Writers, composers, photographers, filmmakers, dramatists, poets, musicians, dancers, artists, socio-political activists flourished and exploded onto the world stage but were denied the opportunity for career advancement in their own homeland. Few other places can boast of such an explosion of talent and impact. It was nothing short of miraculous, given the adversity faced by the people.

The District’s Hyman Lieberman and Marion Institutes were cultural centres of excellence. Down the road the Eoan Group was the launch-pad of many stars such as Johaar Mosaval who began his ballet career there. It was the start of a journey that led to the Royal Ballet Opera School in London and to him becoming a principal dancer with the Royal Ballet.

Indeed, shamefully for the Apartheid government and the City authorities, and tragically for the people of the district, District Six, home of more than 60,000 people was demolished and its people forcibly removed under Apartheid’s ethnic cleansing programme for the City.

The District’s names and achievements roll off the tongue: Abdullah Ibrahim, Basil Coetzee, Lennie Lee, Bea Benjamin, Zane Adams, Hotep Galeta, Alex la Guma, Richard Rive, Rozena Maart, Adam Small, Taliep Petersen, George Hallett, Gregoire Boonzaier, Sandra McGregor, James Matthews and Trevor Jones are just a few of those names.

Johaar Mosaval was born in District Six in Cape Town on 8 January 1928 and was one of nine children in his family. His family descended from Southeast Asian slaves. Taken captive from the Indonesian Archipelago in the 17th and 18th centuries and sold to the United Dutch East India Company (the VOC). Brought to the Cape as the main labour force, from artisans and house servants, to builders and farm workers. Johaar’s story of reaching for the stars and becoming one, is a story of triumph despite Apartheid and adversity.

Dulcie Howes

Dulcie Howes, a prominent figure in the South African dance arena, saw him in a primary school pantomime and organised for him to attend the UCT Ballet School from 1947 to 1949. This was unheard of at that time and came under much criticism and opposition from white people. Johaar was also under pressure from his conservative Muslim family because dance was considered un-Islamic. It was also not an easy scenario for Mosaval to be the only person of colour in the institution and in class. He remembers the time well: “It was the height of apartheid and there was no scope for me. She broke the race barrier by taking me to ballet classes. I had to stand at the back of the class. The white boys in the class would give me sideways glances if I happened to grand jeté myself to the front.”

Regardless of Howes’s efforts, Apartheid prevented Mosaval from pursuing a dance career in his homeland as theatres and stages were for ‘whites only’. But he got a break in 1950 when he caught the attention of two visiting celebrity ballet dancers – Alicia Markova and Anton Dolin. They organised a scholarship for Mosaval to attend the famous Sadler’s Wells Ballet School in London. Within a year he progressed to join the Royal Ballet School and within another year he graduated into the Royal Ballet Company. By 1953 Johaar Mosaval the young man from District Six was well on his way to becoming a ballet dancer of note.

In 1956 Mosaval was promoted to soloist and performed his first solo for the coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II at Covent Garden. She was joined in the audience by an array of royalty from across the world as well as many others world leaders. He says:

“The absolute pinnacle of my career was when I was chosen to dance my very first solo for the Royal Ballet, in the opera Gloriana especially composed by Benjamin Britton for the occasion of the Majesty the Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation.”

By 1960 Mosaval achieved the position of principal dancer and by 1963 he was ranked as principal alongside legendary dancers like Dame Margot Fonteyn, Rudolf Nureyev, Dame Beryl Grey, Nadia Nerina and Svetlana Beriosova. In 1965 he was a senior principal dancer, the first person of colour to hold this position, touring the world with the Royal Ballet, partnering with the most famous of ballerinas such as Margot Fonteyn, Svetlana Beriosova, Lynn Seymour, Merle Park, and Nadia Nerina who was a South African. He was not allowed to dance with Nerina in his home country. He was in ballets choreographed by Frederick Ashton, Kenneth MacMillan, Ninette de Valois, and two South Africans, David Poole and John Cranko.

Compared with Nijinsky

Johaar Mosaval’s brilliance as a character dancer with his own distinguishable impeccable technique placed him in the top league. A critic writing about his performance as Puck in 1967 said; “Puck seems tailor-made for Johaar Mosaval. His apparent ability to pause in the middle of a stupendous scene makes one think of the similar claim made for Nijinsky.” In 1975 Mosaval’s life was transitioning into teaching as he retired from performing and became the first dancer to complete the Professional Dancer’s Teaching Diploma from the Royal Opera House. He had also received the Winston Churchill Travelling Fellowship award from the British Queen Mother, that took him to study contemporary dance and jazz in the United States.

His stellar career with the Royal Ballet lasted 25 years and Johaar Mosaval returned home to Cape Town in 1976 with wonderful memories. He never forgot the Eoan group and before returning permanently he took great delight in being able to perform for home audiences on two occasions in David Poole’s ‘Pink Lemonade’ and ‘The Square’ produced by the Eoan group.

After his permanent return to Cape Town, Mosaval did a guest appearance for Capab Ballet in the title role of Petrouchka – thus becoming the first black dancer to perform in the whites-only Nico Malan Opera House (now Artscape). He was also the first black South African to appear on local television. But while these appeared to be opportunities heralding change, the true reality hit Mosaval in the face.

His permanent return was in the middle of one of South Africa’s most turbulent times as new generations of youth were fed up with a country being run by people and an ideology that put a lid on their dreams of advancement. A national youth uprising broke out starting in Soweto and spreading across the country to Cape Town. Mosaval immediately did something very practical to meet young people’s dreams.

Mosaval opened his own ballet school in 1977 and was employed as the first person of colour to be an Inspector of Ballet under the old Government. He quickly resigned when he found that he had to work within only his own ‘designated race silo’. As a result of his act of defiance his ballet school was shut down by the apartheid regime because it practiced no distinction between ‘races’.

Numerous Awards

Mosaval followed his heart and his non-racial principles in bringing his amazing talent, experience and love of ballet to all young people to release that hidden fire and untapped talent within. He continued to teach wherever he was invited or wherever he could find a place to do so.

Mosaval in accepting an ACT Lifetime Achievement Award both summarised his own sense of accomplishment and fulfilment and, expressed his hopes for future generations –

“Arts and culture has been an integral part of my life, and is an important part of South African heritage, one that we need to showcase. My hope is that young dancers dream to satisfy this hunger for the arts, and that they choose to perform these dreams with excellence, grace and physical beauty.”

These are some of Johaar Mosaval’s awards:

Dancer’s Teaching Diploma at the Royal Opera House (1975)

Winston Churchill Award (1975)

Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee Medal for his services to ballet in the United Kingdom (1977)

Western Cape Arts, Culture, and Heritage Award in (1999)

Western Cape Province – Premier’s Commendation Certificate (2003)

Cape Tercentenary Foundation – Molteno Gold Medal in (2005)

City of Cape Town – Civic Honours Award

The Arts and Culture Trust – Lifetime Achievement award for Dance (2016)

References

Sirhan Jessa: Cultural Heritage Regeneration of District Six – A creative tourism approach; Masters Dissertation – Cape Peninsula University of Technology; (2015)

Horst Koegler; Mosaval, Johaar – Concise Oxford Dictionary of Ballet, 2nd ed; Oxford University Press (1982).

Marina Grut; The History of Ballet in South Africa; Human & Rousseau; Cape Town; (1981)

Denis-Constant Martin; Sounding the Cape – Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa; African Minds; Cape Town; (2013)

Wikipedia; Johaar Mosaval

Hilde Roos; Opera production in the Western Cape- strategies in search of indigenization; Doctorate dissertation; University Stellenbosch; (2010)

Ciraj Shahid Rassool; The Individual, Auto/biography and History in South Africa; Doctorate Dissertation; UWC; (2004)